Adapting to Uncertainty: A Systems Thinking Lens on the Big Beautiful Bill

- Katie Shearn

- Jul 4

- 4 min read

A Call to Evolve Our Business Models for the World We Actually Live In

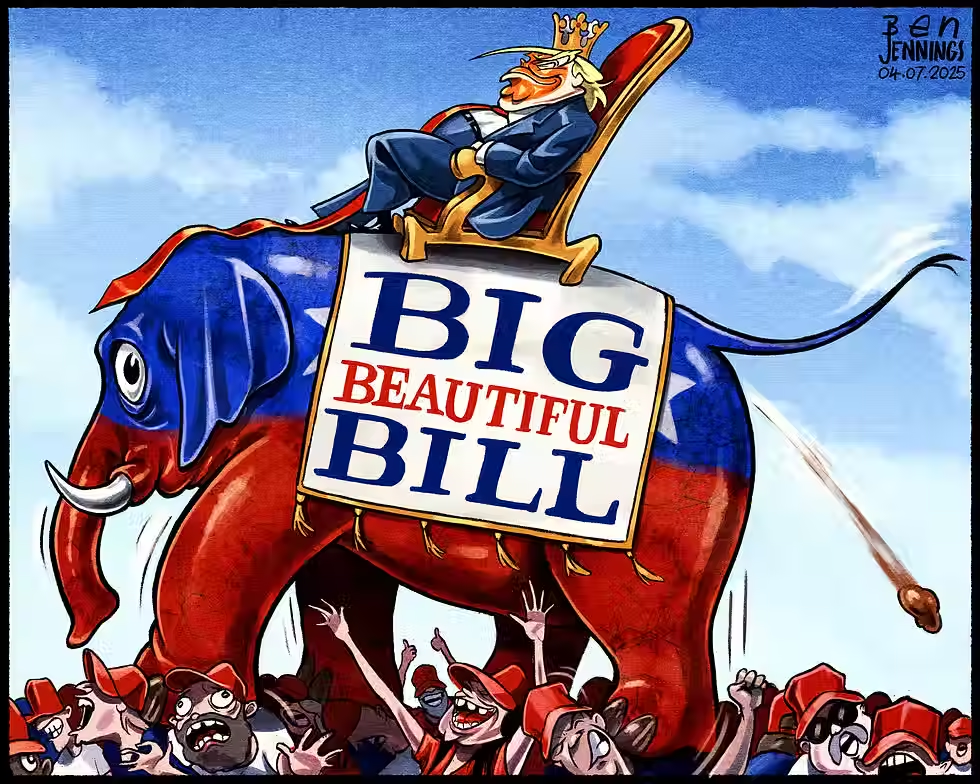

Let’s talk about the fallout from the so-called Big Beautiful Bill….not just what it changed, but what it is exposing.

This bill didn’t just reverse key parts of the Inflation Reduction Act. It's revealing something deeper: Our current business models weren’t built to survive change.

Nearly every company in the renewable energy sector has built its operations around a stagnant model, one that hinges on forecasting, certainty, and the illusion of control. At its core, this model thrives on predictability. Contracts worth billions are signed based on projections that assume precision—down to five-minute energy price intervals.

But here’s the truth: Those forecasts are always wrong. ALWAYS!

They’re wrong because the models don’t account for everything! They can’t, even though they try. Reality is too complex. There are always unseen variables—regulatory shifts, geopolitical instability, technological breakthroughs—that forecasting models fail to capture.

The Big Beautiful Bill, which reversed the tone and direction of the Inflation Reduction Act, just made that failure painfully visible.

Now, the industry finds itself forced to face what it has long denied: We’ve never had certainty. We just wrapped it in spreadsheets and called it strategy.

These models are like weather forecasts. Sure, we can predict that summer will be hot or that winter brings cold. But try predicting the exact temperature, wind speed, and cloud cover for a five-minute window three months from now? Good luck.

Yet that’s exactly what our business models are trying to do—with billion-dollar decisions hanging in the balance.

So who survives?

Companies with deep capital reserves—firms like NextEra Energy, AES, or JP Morgan-backed ventures—who can afford to absorb the volatility.

The ones that get acquired, folded into larger conglomerates, and slapped with a new name no one remembers.

Or the rare few that adapt—not by tightening their grip on control, but by loosening it and building resilient, flexible systems.

It’s moments like these that highlight why systems thinking isn’t just a philosophy—it’s a survival strategy.

Let’s take a simple example:

A renewable energy developer builds a revenue forecast assuming the full benefits of the Inflation Reduction Act—including tax credits, bonus adders, and a predictable investment runway over the next 10–20 years. That single forecast informs everything: PPA pricing, capital stack structuring, investor pitches, and team hires.

The assumption? That the IRA is a stable, locked-in policy environment.

Then the Big Beautiful Bill arrives—reversing course on key incentives.Suddenly, that once-stable boundary collapses.

Now the forecast isn’t just off—it’s irrelevant.

And this isn’t a one-time miss. It reveals a deeper flaw: The business model of “gaining more control over uncertainty” by making misaligned assumptions, like in forecasting, simply doesn’t work in landscapes defined by constant change.

Forecasts are just one piece of a larger system. They’re useful—but when treated as gospel instead of guidance, they create fragility.

This is where systems thinking changes everything.

Systems thinking doesn’t ask you to throw out forecasting.It asks you to use it properly—as a tool for learning, not prediction.

You create hypotheses, test them, and—most importantly—revisit your assumptions through constant feedback loops.

You stop pretending you can outrun uncertainty.Instead, you build your business to breathe within it.

Most companies don’t even compare forecasted prices to actuals. That happens later—if ever—when accounting reconciles the numbers.But by then, it’s too late.

Systems thinking makes uncertainty livable.

It transforms change from a threat into a signal.

It roots operations in adaptable infrastructure—not rigid expectations.

It emphasizes real-time reevaluation, ongoing learning, and systemic awareness.

And as big as this shift feels, it’s not the first time businesses have been forced to reckon with outdated models in the face of rapid change.

During the Great Depression, a massive economic shock wiped out countless businesses.But not all.

Some survived because they had deep cash reserves and broad industrial reach—companies like General Motors, DuPont, and JP Morgan were able to weather the storm simply because they could absorb more risk than others.

But others survived—and even thrived—because they adapted:

Procter & Gamble pivoted from luxury products to radio advertising and household staples, meeting families where they were.

Kellogg’s doubled down on advertising and innovation, promoting ready-to-eat cereals as consumers moved away from labor-intensive meals.

IBM shifted from selling luxury tabulating machines to offering affordable services for government and defense sectors, completely repositioning its value.

These companies didn’t just “ride it out.”They changed how they operated.They focused on real needs in real time, responding to uncertainty not with tighter control—but with better listening, clearer thinking, and bolder action.

If you have influence over how your organization operates, take a hard look:

Are you using your tools to understand the system?Or are you using them like magic wands, hoping to outguess the unpredictable?

The future belongs to the ones who get this:

The future isn’t for those who predict it—it’s for those who are ready to meet it.

Comments